Tetyana Pekar

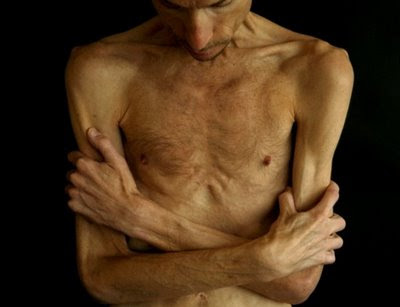

Anorexia nervosa (AN) affects 0.1-1 percent of the population and has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric illness1. Anorexia doesn’t discriminate against age, sexual orientation, gender, or race. Nor is it limited to Western countries or middle-class white girls.

Occasionally, severe cases of anorexia nervosa gather media attention and a lot of controversy. At the heart of the matter is an ethical dilemma: whether and under what circumstances should patients be force-fed or allowed to starve themselves to death?

Several such cases have recently been publicized. The first case is a 32-year-old former medical student from Wales2, known only as "E." E hasn’t had solid food for more than a year and has a body mass index (BMI) of 11-12—a normal BMI is 20-25. Although she does not want to die per se, E, above all, does not want to be fed. Her chances of recovery are between 10-20 percent, according to a consulting psychiatrist and eating disorder specialist. Those who know her well—including her parents—oppose further treatment and believe she deserves the right to die with dignity.

The second case3 is of an anorexic known as "L." L is 29-years-old, and in the last 15 years, she has spent 90 percent of her time as an in-patient. She weighs just 45 lbs. Like E, L did not express a desire to die, but stated that “her severe anorexia ‘did not allow her to eat.’ ”

Typically, such ethical dilemmas are approached by attempting to grant the competent patient’s wishes, helping the patient, and considering the interests of all involved. The situation in anorexia nervosa, however, is much more complex.

Anorexia nervosa patients are typically not psychotic and often do not pose an imminent risk to themselves—they are generally not suicidal, and don’t express an overt desire to die, although their actions certainly lead to a slow death. They are usually competent, and quite rational, they are “just unable" to eat enough to maintain a normal weight.

Interestingly, the High Court judges ruled differently in these two cases. In the case of E, the judge ruled that she should be force-fed, alluding to the fact that E may not, at this time, fully appreciate that we only get one chance at life. In the case of L, however, the judge concluded that although nutrition and hydration should be offered to L, staff were not permitted to use "force" to administer food, water, or medicine.

Charlotte Green4, a 35-year-old anorexia nervosa patient who spoke to the UK newspaper The Telegraph in response to these cases, stated that the duration and severity of the illness are important factors that must be considered whenever the decision to force-feed is made.

For Green, who has been severely sick for over a decade and spent most of that time in treatment, the prospects of recovery are grim. “I have been ill for 15 years and it only gets harder… I want to be allowed responsibility for what happens next,” Green said.

Starvation alters the way our brains function. It is conceivable that once re-fed, these patients will be thankful for the decisions made on their behalf; certainly, there are patients with anorexia nervosa who were force-fed at one point and are now recovered. But, the opposite scenario could just as easily be true: forced feeding could cause more suffering for the patient and the family, as caregiving for a patient that refuses treatment is incredibly difficult.

What if it is too late? We cannot force patients to recover—force feeding for life is unsustainable.

Green—who has been sick for 15 years—doesn’t want any more money wasted on treatment, wasted because she doesn’t “engage” in it. “They [the psychiatrists] can make me pretend as much as they want to—but in the end I’m only pretending,” she adds.

Shouldn’t patients in these situations be allowed to die with dignity? What are doctors to do when patients don’t want to die, but cannot eat? Refuse to eat. How do you treat someone for whom death is a better alternative than eating?

This is the illness talking. Winning. But, if treatment for decades has failed, does it ever come to a point where clinicians and parents can say, what’s been done has been done, we can’t do any more?

An astute commentator on a Facebook page for FEAST (Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment for Eating Disorders) wrote that “the biggest ethical issue here is in the failure to treat adequately while this woman (referring to the case of L) still had hope,” adding that “there may come a point of no return in some people’s AN.”

Some, like Laura Collins, author of Eating with Your Anorexic, believe that allowing these patients to die is akin to murder. On the same Facebook thread, Collins wrote “To hospitalize without restoring normal health, to depend on the mentally ill patient's assessment, and to believe that the real person in there 'wants' to die [is murder]. We would do better for someone in a coma. This is a basic misunderstanding of the nature of anorexia nervosa. If they 'allow' her illness to kill her they are making themselves more comfortable, not her—she only gets one life and it is not her fault or choice that they've failed her so thoroughly (emphasis mine).”

Although caregivers are not required to sacrifice themselves to save someone, especially if their prospects of recovery are grim, we cannot ignore or deny the important role that strong emotional reactions may have on the physicians' and caregivers' decisions with regard to treatment. To what extent are the decisions made by the judges based on making themselves, and the treatment team, feel comfortable?

Historically, patients with anorexia nervosa have achieved a reputation of being notoriously difficult to treat. Resistant, deceitful, manipulative, greedy, selfish, and narcissistic are just some of the words that physicians have used to describe AN patients5.

Caring for a patient with AN6 can be emotionally and financially draining, and this has grave implications for how patients are treated; particularly in cases where the decision to force-feed becomes unavoidable.

The concern is that treatment might be withheld because patients are perceived as being difficult. Hebert and Weingarten, in their analysis of the ethics of forced feeding in anorexia nervosa7, worry “that an analysis of futility that uses only abstractions such as benefits and burden may simply be a post-facto rationalization of the strong negative feelings such patients evoke in others.”

If the patient with anorexia nervosa is deemed incompetent, then is it up to the parents and physicians—who are likely mentally exhausted from years of treatment—to decide? If, on the other hand, the patient is deemed competent, but not suicidal—with no intention to die, but no ability to do what’s necessary to survive—do we grant the patient ability to refuse food when food refusal is at the very heart of this disorder?

Appelbaum and Rumpf, in their paper titled Civil Commitment to the Anorexic Patient8 write that “denial is such an integral part of the disorder, even many anorexics who can recite lists of adverse outcomes associated with their disorders are, at the same time, quite sure that none of these events will ever happen to them. Although these patients are not globally incompetent, they may well be incompetent to make decisions about providing themselves with basic sustenance or obtaining medical care.” Is this letting anorexia win or is it acknowledging that this deadly illness is often intractable?

For many of these cases perhaps it is too late. But one thing is clear: in all of these cases, those in charge of treatment (or financing treatment) have failed; even just by letting their patient’s disorder get this far. To deny someone treatment—as many insurance companies do—is to fail patients; to discharge patients when they are not ready because treating them is too hard, is to fail patients. To belittle, dismiss and minimize the grave nature of this illness is to fail these patients.

Inability to eat enough to maintain a healthy weight is at the center of this disorder and allowing patients to refuse food under the guise of autonomy is admitting the illness won.

We can do better. We have to. We need to provide better treatment—and provide it early on, before eating disorder behaviours become engrained. We need to educate health care professionals, medical students, families and partners about this disorder, because recovery is possible and death is preventable.

References

- Smink, R.E.F., van Hoeken, D. and Hoek, W.H. (2012). Epidemiology of Eating Disorders: Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep 14(4): 406-414.

- Anorexic medical student should be fed against her will, judge rules. (2012, June 15). Telegraph. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/9334118/Anorexic-medical-student-should-be-fed-against-her-will-judge-rules.html

- Anorexic woman not be force-fed, judge rules. (2012, August 24). BBC News UK. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-19369239

- Donnelly, L. (2012, August 5). Anorexia: ‘You can’t force me to live’. Telegraph. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/9451734/Anorexia-You-cant-force-me-to-live.html

- Thompson-Brenner, H., Satir, D.A., Franko, D.L. and Herzog, D.B. (2012). Clinician reactions to patients with eating disorders: a review of the literature. 63(1):73-8.

- Treasure, J., Murphy, T., Szumkler, G., Todd, G., Gavan, K., and Joyce, J. (2001). The experience of caregiving for severe mental illness: a comparison between anorexia nervosa and psychosis. Soc Psychiatry PsychiatrEpidemiol36(7):343-347.

- Hébert, P.C. and Weingarten, M.A. (1991). The ethics of forced feeding in anorexia nervosa. CMAJ 144(2):141-144.

- Appelbaum, P.S. and Rumpf, T. (1998). Civil commitment of the anorexic patient. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 20(4):225-230.